Officially founded in 2023, our organization conducts experiments across several different countries. We partner with experienced and verified farmers, an agro-consulting company, state-of-the-art laboratories, scientists at specialized universities, and experts in statistical data processing to help farmers reap the most out of their fields without harming the environment.

According to relevant studies, agriculture accounts for up to 30 percent of total anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. That is why technological efficiency in agronomy is so important—literally every percent.

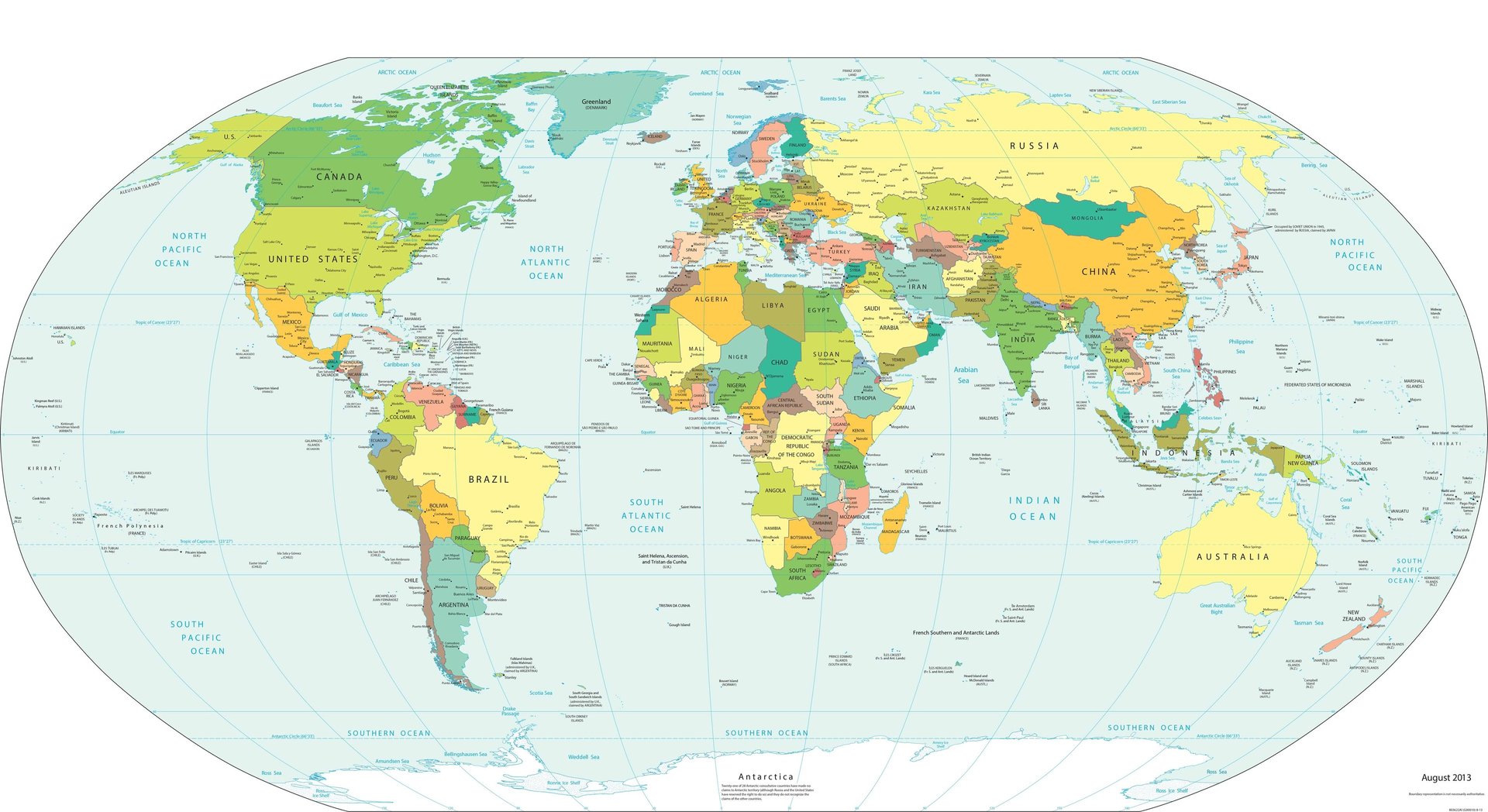

Consider this. The area of land occupied by peas cultivation on the Earth is more than 10 million hectares (about 25 million acres). If our study results in even a 1% increase in the efficiency of growing peas, that automatically frees up approximately 100 thousand hectares of fertile land, which, in turn, is equivalent to the area of 293 New York City's Central Parks.

Along with the land, thousands of tons of fertilizers, chemicals, fuels, etc. are released. Multiply this result by 20 years and you’ll understand how science can affect the ecological efficiency of humanity!

Dariia Lukyanenko

Let's get

[ aposteriori ] founder

Email: dariia.lukyanenko@gmail.com

Phone: +1 (413) 768-7765

Check out the story of how it all started!

in touch!

How

Further, an amazing incident introduced me to the founder of AgroAnaliz, one of the most advanced agro-consulting companies in Ukraine, Vadym Dudka—an experienced professional in agricultural science. I told him about things I saw on the farm and he confirmed that among farmers, the opinion that calcium deficiency leads to necrosis of Chinese cabbage prevails; however, he and his team were questioning this belief due to the lack of properly conducted studies. I really wanted to study this problem, and Vadym kindly provided us with access to their laboratory and their client’s field so that we could conduct a full-fledged experiment. A lot of people were involved in the study: the principal agronomist, specialists from an agro-consulting company, and scientists from the local agricultural university—and we worked together to develop the plan for the experiment.

it all started

For several generations, my father’s family lived in Middle Asia—that’s why we still preserve some of the Middle-Asian culinary traditions. Following one of such family traditions, we salt kimchi in large clay barrels every fall to enjoy it in the wintertime. Closer to mid-October, we always go to local farmers and load the car with Chinese cabbage to capacity. On one such trip, I came across several massive piles of discarded cabbage, which, weirdly

Several months later, in the fall of 2021, we got quite interesting results. We showed the possibility of obtaining a high and healthy yield of Chinese cabbage with no use of calcium nitrate at all. Funnily enough, calcium led to a decrease in quantity and quality of yield in some cases. We realized (and proved it scientifically) that farmers applied calcium nitrate, the product of natural gas conversion, in large doses for no reason—simply because of the lack of scientifically-proven data. It was quite a revelation for us.

Given that Chinese cabbage is one of the five most common vegetables in the world, it is safe to say that humanity pointlessly digs thousands of tons of calcium nitrate into the ground every year, focusing only on pseudoscientific myths.

This experiment inspired me to conduct new studies, which led me to create the Aposteriori project. And that’s how it all started!

enough, looked appealing and perfectly healthy. I asked the farmer why he threw away so many goods—and he approached the pile and cut several cabbage heads in halves, pointing dark spots on the internal leaves. As it turned out, the whole pile was affected by internal necrosis; and that’s how I first heard of this disease of Chinese cabbage. The farmer added that he probably did not apply enough calcium fertilizer, since it is the calcium deficiency that leads to necrosis in Chinese cabbage, according to industry experts’ opinion.

[ choosing the ]

Topic

Selecting the research topic is one of the most important stages of our work. The research subjects do not come to us in the form of arbitrary insights or individual farmers’ requests—they emerge as a response to a lack of reliable scientific data. That's how it usually works ->

An agro-consulting specialist of our partnering company encounters an unfamiliar problem on a client's project, after which they search the company's database. If reliable data cannot be found, then this problem is submitted to the expeditious technical council.

In case the council is not able to give a definite answer, the problem is posted in a specialized closed chat of farmers, the company's clients—and these are 500+ highly qualified specialists in crop cultivation from 7 countries.

If the discussion points cannot be backed up by reliable research on the problem of interest, we initiate an extensive search of scientific databases.

If only all these steps did not lead us to a source of reliable scientific data, the topic appears in the list of prospective research topics.

[ 1 ]

[ 2 ]

[ 3 ]

Study

If, after a thorough analysis of the scientific literature, the [ aposteriori ] team concludes that the topic has not been sufficiently studied, we set about developing an experiment plan. It’s similar to designing an architectural plan for a building; we have to mind dozens of nuances: property selection, correct randomization, dosage accuracy, human factor, one-factor comparison, including but not limited to uniformity of insolation, soil fertility map, field topography, and so on...

[ designing the ]

Experiment

To make the results of our studies applicable to different climatic conditions and soils, we have the opportunity to conduct the same experiment simultaneously in different locations: the United States, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan. Thanks to our network structure, we are able to maintain minimal administrative costs—so more is yet to come!

[ conducting the ]

Results

When the experiment is finished, it’s time to collect data and process the results. After our experts check the statistical significance of the results using special computer models, we publish them in the public domain so that everyone—from private farmers to agro-consulting companies—has access to the knowledge and can apply it to their fields.

[ evaluating and sharing the ]

Fear not, there is a big idea behind this clumsy, hard-to-pronounce name (pronounced uh-pAWs-teh-ree-oh-ree), which surprisingly isn’t out of a desire to make our lives harder. Aristotle developed two philosophical types of knowledge: a priori and a posteriori. The latter is less known than the former, but we believe that it shouldn’t be. A posteriori knowledge is synonymous with a scientific one, as it is derived strictly from empirical evidence. In naming the organization [ aposteriori ], we underline that the knowledge we publish is derived from evidence and certainty only. We would never publish results that we are not completely sure of, which is apt considering our commitment to scientific objectivity.